The gaming, film and virtual reality industries rely heavily on recorded samples for sound design. This has inherent limitations since the sound is fixed from the point of recording, leading to drawbacks such as repetition, storage, and lack of perceptually relevant controls.

Procedural audio offers a more flexible approach by allowing the parameters of a sound to be altered and sound to be generated from first principles. A natural choice for procedural audio is environmental sounds. They occur widely in creative industries content, and are notoriously difficult to capture. On-location sounds often cannot be used due to recording issues and unwanted background sounds, yet recordings from sample libraries are rarely a good match to an environmental scene.

Thunder in particular, is highly relevant. It provides a sense of the environment and location, but can also be used to supplement the narrative and heighten the tension or foreboding in a scene. There exist a fair number of methods to simulate thunder. But no one’s ever actually sat down and evaluated these models. That’s what we did in,

J. D. Reiss, H. E. Tez, R. Selfridge, ‘A comparative perceptual evaluation of thunder synthesis techniques’, to appear at the 150th Audio Engineering Convention, 2021.

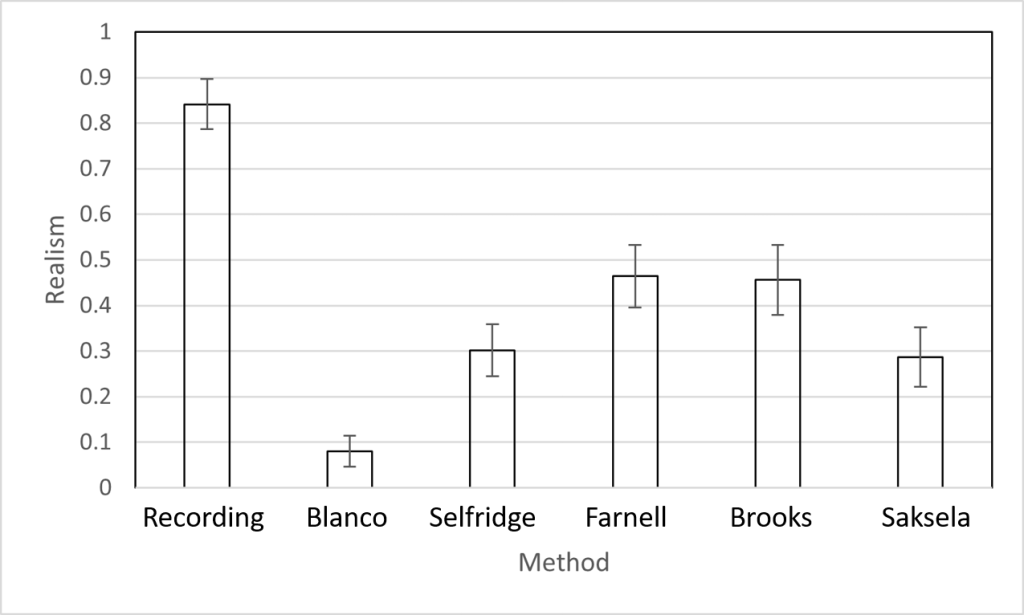

We looked at all the thunder synthesis models we could find, and in the end were able to compare five models and a recording of real thunder in a listening test. And here’s the key result,

This was surprising. None of the methods sound very close to the real thing. It didn’t matter whether it was a physical model, didn’t matter which type of physical modelling approach was used, or whether an entirely signal-based approach was applied. And yet there’s plenty of other sounds where procedural audio can sound indistinguishable from the real thing, see our previous blog post on applause foot .

We also played around with the code. Its clear that the methods could be improved. For instance, they all produced mono sounds (so we used a mono recording for comparison too), the physical models could be much, much faster, and most of the models used very simplistic approximation of lightning. So there’s a really nice PhD topic for someone to work on one day.

Besides showing the limitations of the current models, it also showed the need for better evaluation in sound synthesis research, and the benefits of making code and data available for others. On that note, we put the paper and all the relevant code, data, sound samples etc online at

And you can try out a couple of models at

- https://nemisindo.com/app/main-panel/thunder.html

- https://www.kaistale.com/blog/140809thunder/index.html (you need patience for this one; takes about a minute)